Lord Fairfax, writing to the Speaker of the House of Commons from Selby on 26 January 1643 reported on his success in taking Leeds (23 January 1643) and Sir Hugh Cholmley’s action at Guisborough, declaring that a Royalist force of 600 horse and foot had been defeated,

…Yesterday Intelligence was brought to me that the Earl of Newcastle hath drawn down all his Forces from the South Part of Yorkshire…the certain Cause I do not yet know, but suppose it is to meet the Arms and Munition coming from Newcastle, or to prepare for the Queen’s Entertainment at York, which is much spoken of. I shall carry a vigilant Eye upon his Designs, and endeavour to prevent them, so far as can be expected…

Parliamentarian Sir Hugh Cholmley (1600-57)

Major G.R.H. Cholmley & Mr H.J.N.Cholmley

Cholmley’s parliamentarian force, under the command officer of horse, Captain Richard Medley, or Mildmay, marched down the road from Guisborough to Marton, along Ladgate Lane, to Yarm and Egglescliffe, where it was hoped to stop or at least delay the Royalist convoy heading for York. Medley’s did not have long to wait.

The small town of Yarm, along with Croft, Piercebridge and Barnard Castle to the west, was the lowest of four important medieval bridge crossing points of the R.Tees. Yarm bridge carried the main road north to Stockton and on to Sedgefield and Durham, and south to Thirsk and on to York. Most of its inhabitants would have been involved in agriculture, and the carrier trade, both by road and river, that had developed based on the export of grain, wool, dairy products, hides fishing and salt.

Yarm & Egglescliffe, c.1771

Jeffrey’s Map of Yorkshire, 1771 (detail)

Yarm and its important medieval stone bridge crossing of the River Tees was,

… in this year (1643) was for a short time garrisoned by 400 of the parliament forces…

For a few precious days from mid- to the end of January 1643 the parliamentarians probably prepared their defences. Likely the ‘greater work’ was still maintained and useable, referred to in Sep 1640 during the Bishops’ Wars, built on,

a hill of great advantage close before the bridge where Sir Wm Pennyman had begun a small work

It had been constructed to take two batteries and two pieces (of artillery) and to overlook the approach road to Yarm Bridge from Stockton to the North. The Parliamentarians could have placed artillery within it, as well as actually on the narrow bridge itself, spanning the broad and deep valley of the River Tees, in order to deter an attempted crossing and passage between Egglescliffe and Yarm.

Building of a ‘work’, or artillery emplacement in the mid-17th century

Drawing by Beck, S. from Barratt, John 2000 Cavaliers: The Royalist Army at War 1642-1646, p.62

Parliamentarian Captain Medley and his forces had seen some limited action around York and their morale probably high following their recent victory at Guisborough. However, their task was a difficult one and the parliamentarian command was no match for experienced professional commanders (later Lieutenant-General) James King and the Lord George Goring and the larger force that was about to hit them from the Egglescliffe side of Yarm bridge on 1 February 1643.

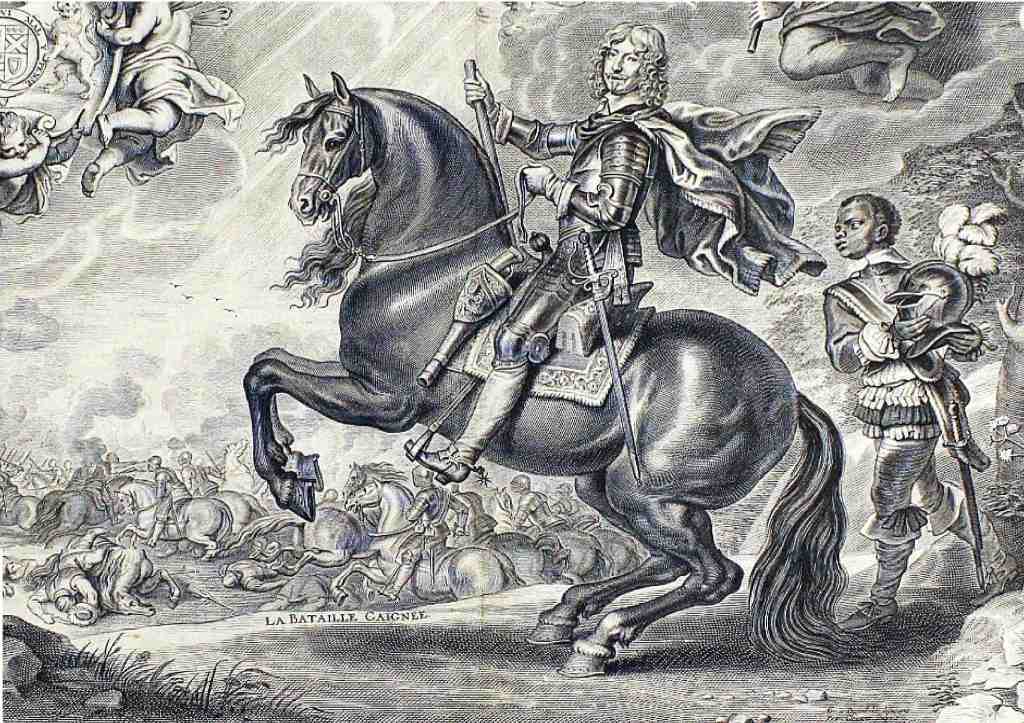

General James King, 1589-1652

Private Collection

VAN DYCK, The Lord George Goring (1608-57)

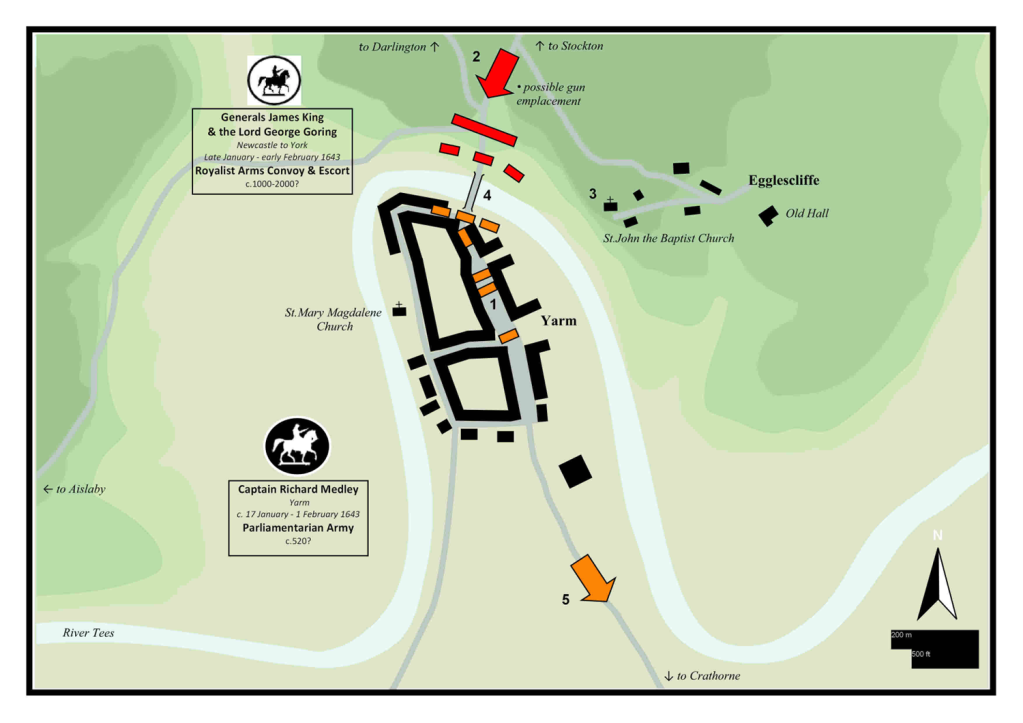

Battle of Yarm, 1 February 1643

Conjectural deployments, Phil Philo, 2022

1.The victorious parliamentarian army from Guisborough entered Yarm and made preparations to stop the expected royalist arms convoy from Newcastle. The billeting of nearly 500 soldiers in and around the town would have been a great burden on a population perhaps half that size. 2. The advance guard of the royalist convoy, commanded by the very experienced Generals King and Goring, approached from the north. The Royalist convoy probably took the route from Newcastle south, through Chester-le-Street, Durham, Sedgefield and on to Stockton-on-Tees. From there they would have taken the main road to Yarm, through what is now Eaglescliffe and Preston Park and on to the small settlement of Egglescliffe. 3.Royalist probably quickly overcame any parliamentarian out-guards on the north side of the River Tees and at the gun emplacement at Egglescliffe if the Parliamentarians had put it into service. A soldier, ‘slain here at the Yarm skirmish,’ was probably killed in this action and buried 1 February 1643 at Egglescliffe. Having taken control of Egglescliffe the Royalists would have had a fine prospect from the church of Yarm, its bridge, other possible crossing points of the River Tees, and the disposition of the enemy’s forces below them. 4. Perhaps after softening up by an artillery barrage & small arms, the royalist foot and dragoons made a direct assault on the narrow bridge. 5.Royalist accounts suggest a swift and merciless attack in which the enemy were,

“…totally routed…” and “…utterly defeated…”

One account describes how the Royalists,

“…fell upon them, slew many…”

and the Royalist victory appears to have been comprehensive and a disaster for the Parliamentarians. As well as casualties around the bridge, there were probably others as a result of running fights through the streets and assaults on buildings and houses being used as cover by the defenders. Fleeing parliamentarians pursued by royalist cavalry.

The Royalists, “…march’d on to York with their Ammunition, without any other Interruption.”

Reconstruction of the drawbridge on Yarm Bridge, c.1643

Phil Philo 2018

The engagement at Yarm in February 1643, like the earlier one at Piercebridge in December 1642, clearly showed the strength of the Royalists in the North, their ability in arming and supplying of their field armies from continental imports through Tynemouth and Newcastle and, in those early months of the Civil War, the inability of the Parliamentarians in the North to field a sufficient force to keep the Royalists at bay.

The settlement at Yarm was again in Royalist hands after its brief occupation by Parliamentarian units.

These were obviously anxious times for the local people, as well as the Royalist soldiers and sympathisers/supporters. There was also the possibility that other ‘flying’ Parliamentarian units from Fairfax’s, Hotham’s and Cholmley’s forces from the South would attempt to bar future crossings of the River Tees at Yarm by Royalist arms and military convoys. To guard against this, a small force of Royalist soldiers and engineers was probably left at Yarm for a few days whilst the main convoy continued its journey to York, as the stone bridge appears to have been altered so as to make its defence easier. The northern arch on the Egglescliffe side of the river was broken through and a wooden drawbridge created.

A few weeks later, on 22 February 1643 at Bridlington, Queen Henrietta Maria landed from Holland with further arms and supplies for the Royalist cause.

Parliamentarian commander Sir Hugh Cholmley held negotiations with her and changed sides to the Royalists on 25 March 1643, leading a very successful though eventually ill-fated fight against his previous employers. Having joined up with the Earl of Newcastle in York Queen Henrietta Maria set off with a large force to reinforce the King at Oxford.